Internet of Things

Did I lock the car?

Exploring device movement as notification in the context of a connected car key.

A project with

Josefine Hansson, Philip Lehning, Stephanie

Neumann, Thanita Thapphasut

What we did

problem framing, fieldwork, interaction design, physical

prototyping, electronics, programming, user testing

My role

researcher, interaction designer, physical prototyper, electronics prototyper

Brief

How can people become aware of a system’s possibilities or status – within a “heterogeneous, fluid, and often invisible infrastructure”? And how do we express these possibilities without it being “intrusive, annoying or ruining the atmosphere of a setting”?

We were asked to consider an existing or near-future Internet of Things (IoT) scenario, and to explore ways in which the product or environment could let itself be known to us.

Rather than designing the ultimate IoT experience, the point was to generate multiple variations. Additionally, we were to avoid the use of text, symbols, or spoken language.

Fieldwork

Our group decided to look into the opportunities and challenges of smart car keys, finding inspiration in one group member’s story of how his wallet was stolen from his van, which he had forgotten to lock. It happened while he was working as a deliveryman, constantly going in and out of his vehicle, and made him wish that the van would just know when to lock itself.

To better understand the behaviors and habits surrounding locking and unlocking the car, we spent time engaging in participant observation, conducting informal interviews with family and friends, and watching people in parking lots.

From our research, it seemed most people had established ways of making sure they’ve locked the car, and weren’t really bothered afterwards. However, there also seemed to exist a small group of people that wouldn’t stop worrying – and we chose to aim our efforts at them.

Prototyping

Initially, our thoughts had revolved around the broad context of a connected car key, along with its practical, social, and environmental aspects. Should my key notify me that another family member just unlocked the car? Could the car key somehow reflect current traffic conditions? A key that won’t open the car, telling me to go by bicycle instead?

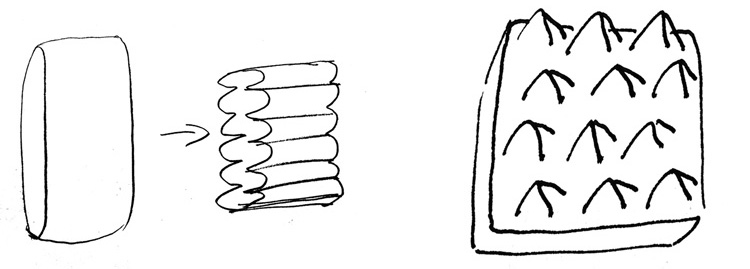

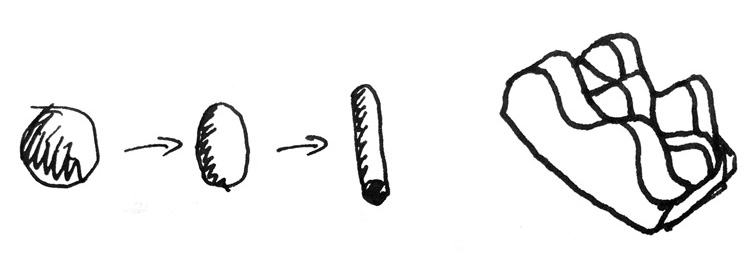

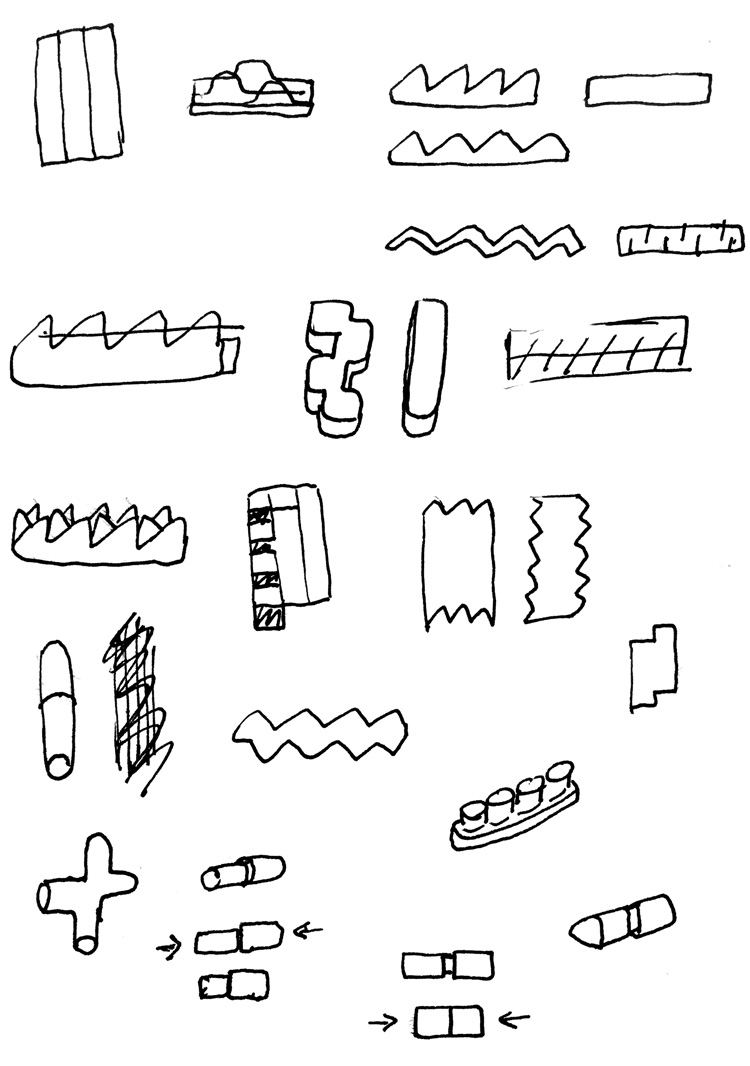

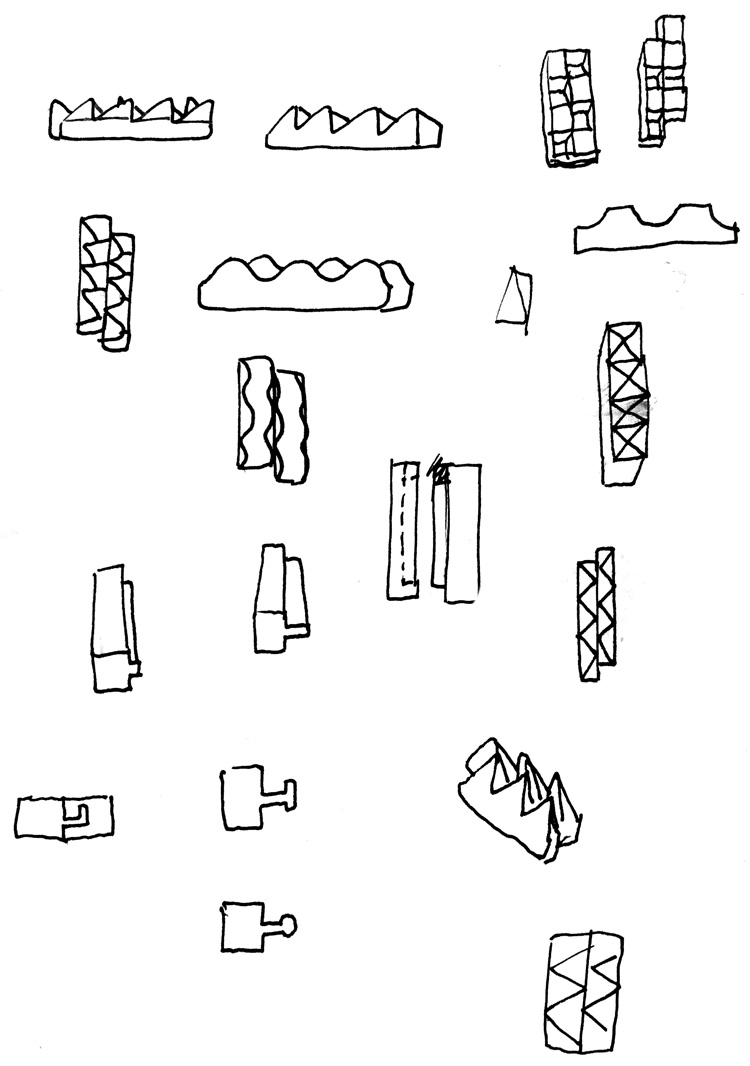

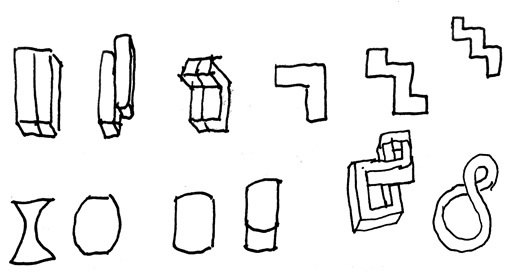

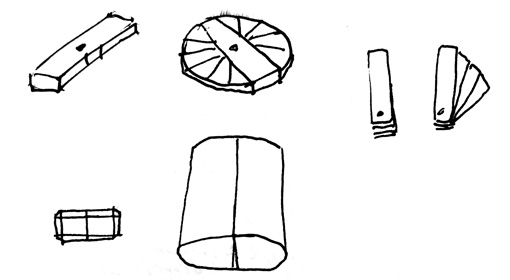

Eventually, as the scope narrowed, the project turned into a kind of study of what different forms of device notification could feel like.

We were curious if it would be possible to mimic the feeling of reassurance you might get from patting down your pocket to check if you have your phone, wallet, or keys with you. What if you could know if you’ve locked the car, just by touching the key in your pocket? Or – if the car would lock itself – could the key shift in shape or tactile sensation to indicate the change?

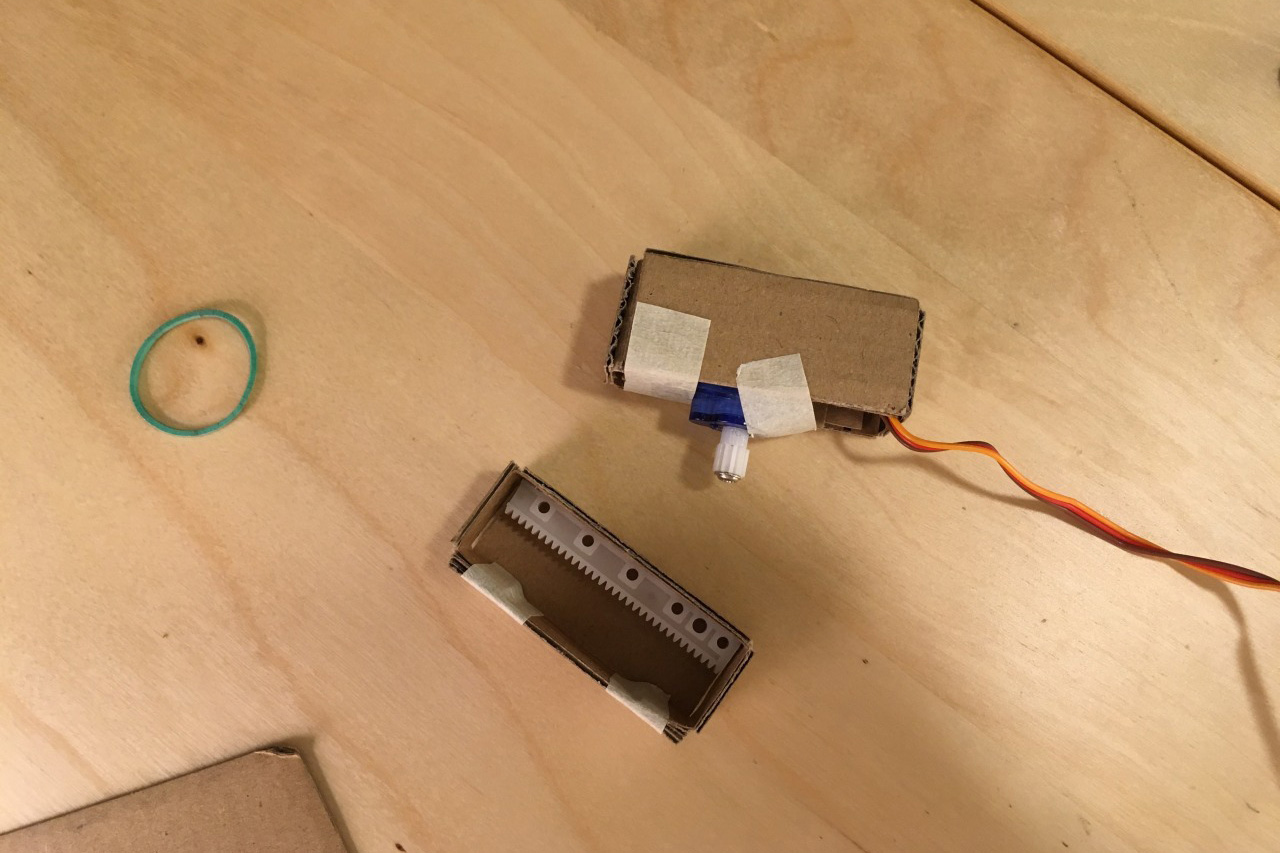

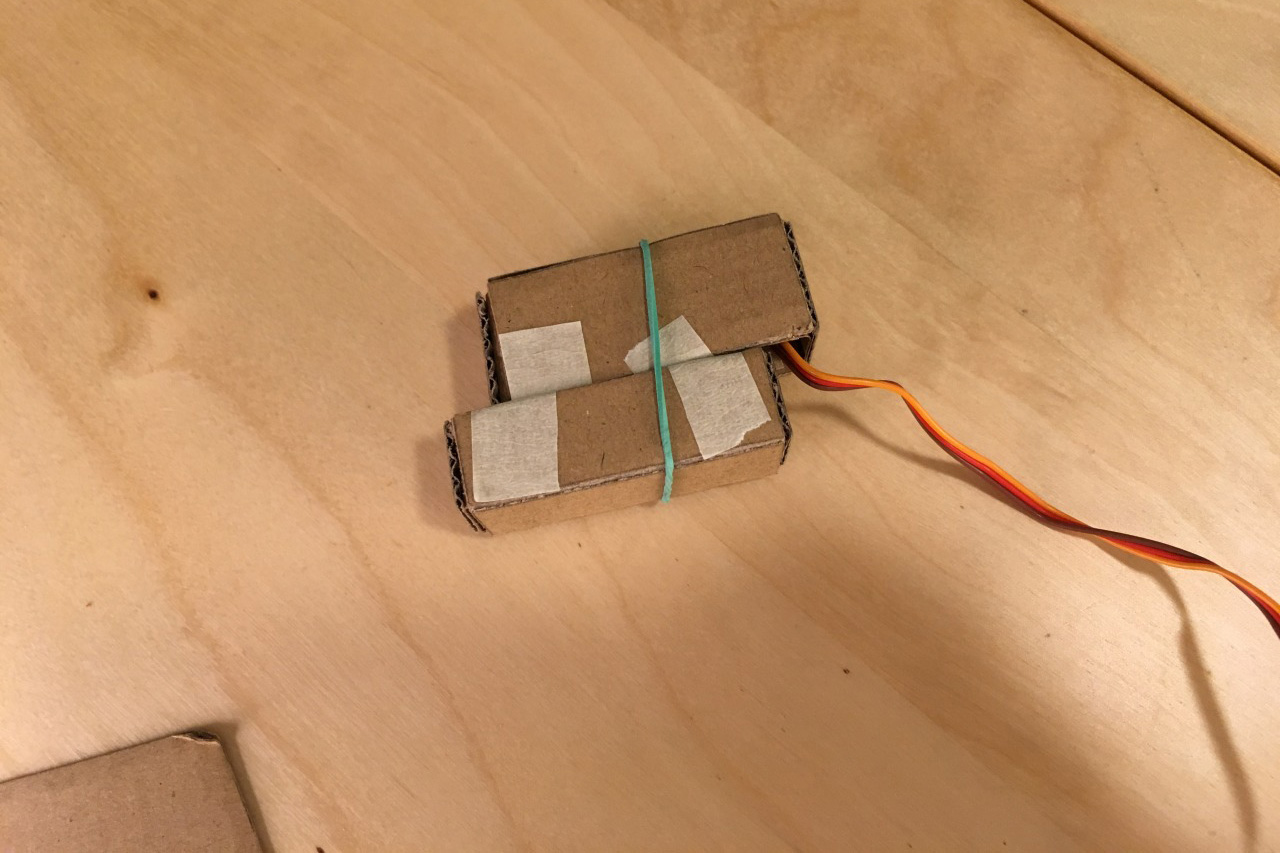

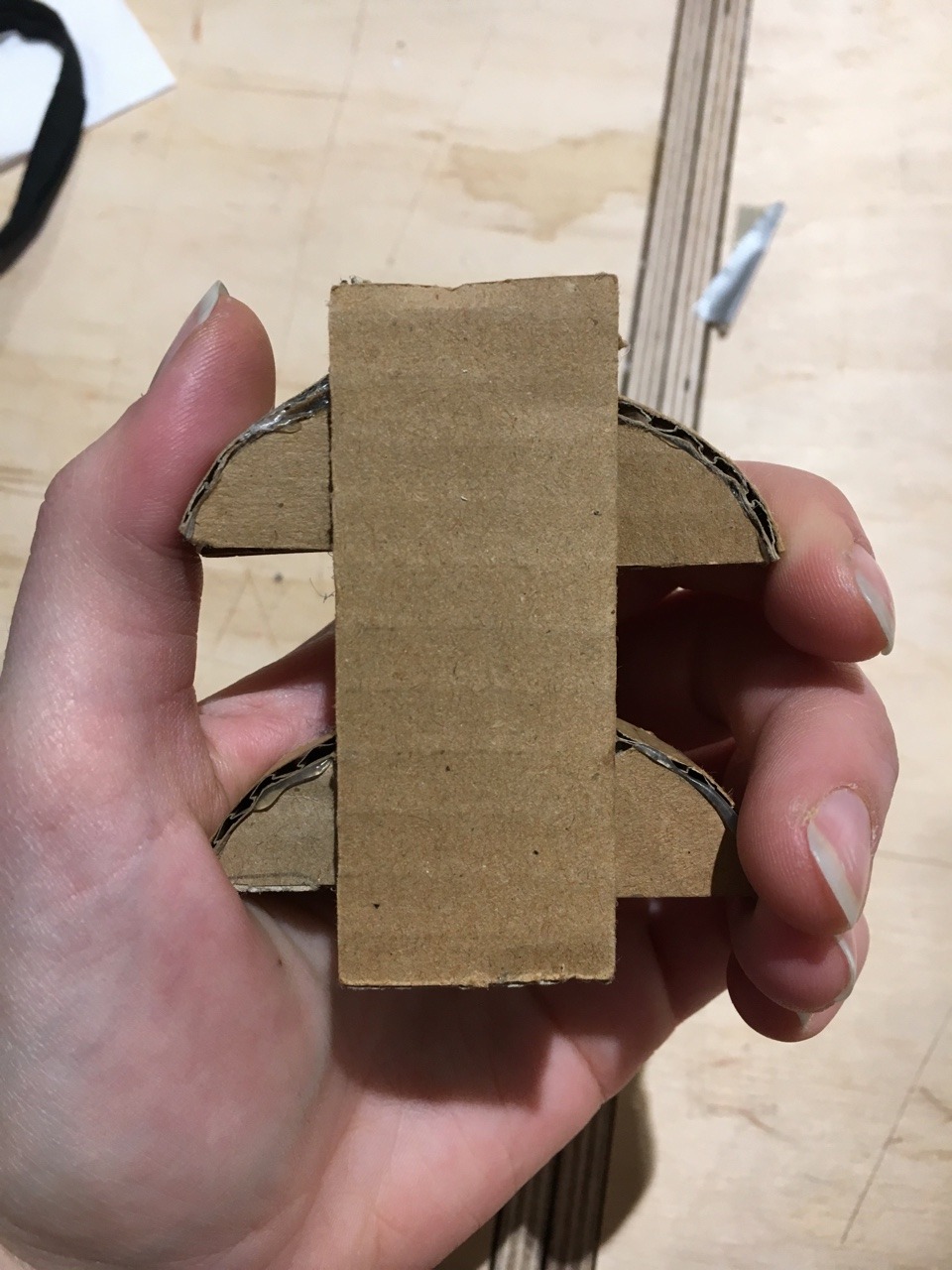

An iterative process followed, with several rounds of sketching with electronics and code, developing quick prototypes, testing with users, and discussing the results.

Although we briefly explored sound and light as cues, most of the experiments dealt with device shape and device movement (linear, rotational, and vibrational). By asking people – mainly university students – to put the prototype in their pocket, we could observe their reactions, and talk to them about the experience.

The most surprising insight was how elusive the calibration of movement turned out to be, in order to make it useful as notification. In testing, it was either too subtle, and not felt at all, or too strong, and perceived as weird, or even unpleasant. Some described the feeling as “having a small animal” in their pocket. The fact that the movement was unanticipated, rather than a direct response to user action, possibly affected the experience, making the device seem to have a life of its own.

For us, as designers, dealing with movement as notification was largely unpredictable, with much fewer design conventions to fall back on – at once hinting at an interesting opportunity within the field.