Service design

How could homecare nurses collaborate with remote doctors?

To begin with, let nurses and doctors meet and talk to each other.

A project with

Barith Ball, Garba Habila, Hafsa Mire, Alison

Thomas

In collaboration with

Innovation Skåne and three municipal

nurses working in the north of Skåne

What we did

problem framing, ethnography, service design,

co-design workshop, service prototyping, stakeholder report

My role

researcher, service designer, visual designer,

prototyper, illustrator, animator

Brief

Having talked to nurses involved in homecare, staff from Innovation Skåne, the regional innovation unit, had concluded that a significant number of physicians’ visits might be avoided, if there was a way for patients to be assessed remotely.

Ideally, it would save time for nurses, spare physicians the travel, and lead to sooner treatment for patients. In the long run, a better use of resources should lead to better healthcare for more people.

Our task was to prototype a service around the idea of remote assessment in homecare, paying specific attention to the needs of municipal nurses.

Background

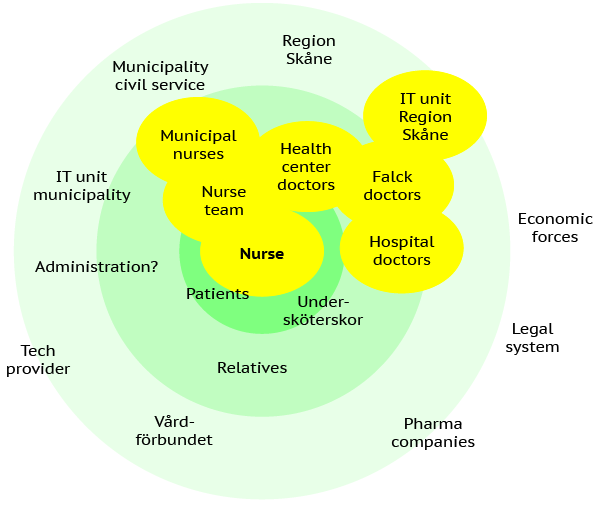

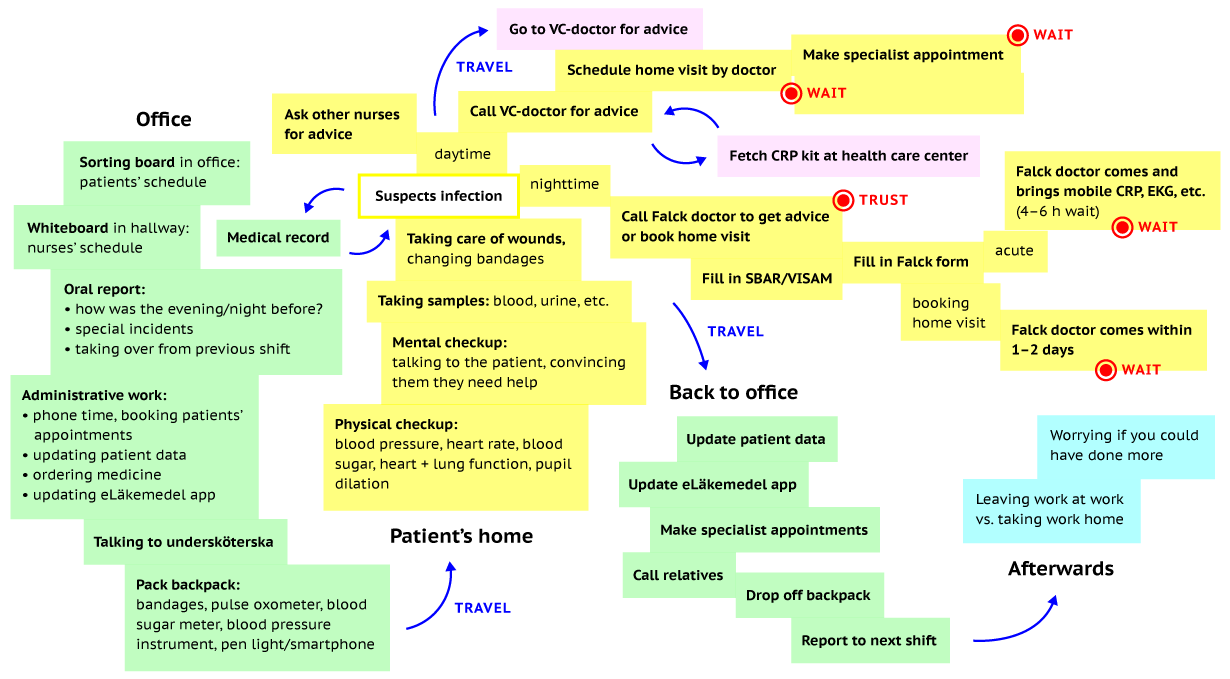

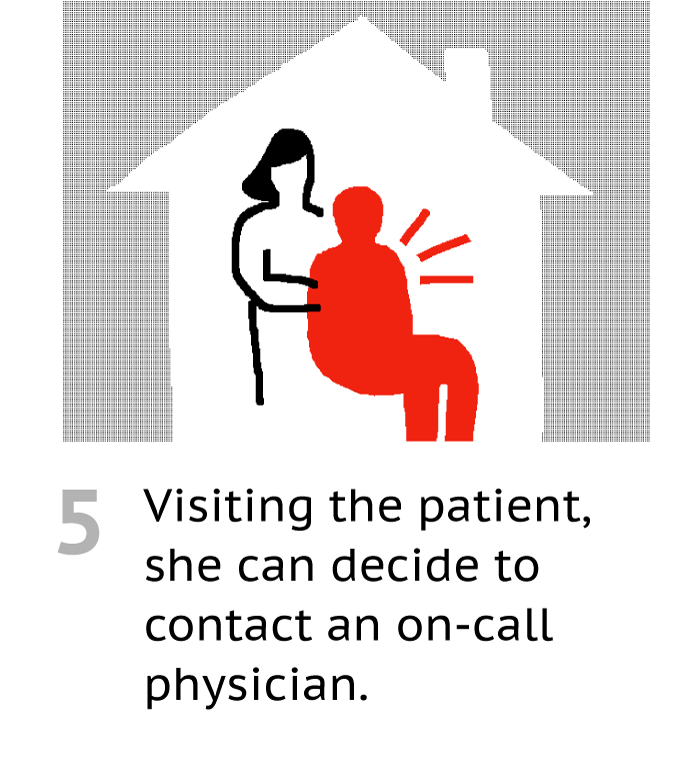

Nurses employed by the municipality take care of patients aged 75 years and older, who have three or more chronic diagnoses and suffer from periodic weakness. Working alone, the nurses visit their patients regularly in the patients’ homes or in retirement homes.

Unlike their counterpart at healthcare centers or hospitals, homecare nurses don’t experience continuous support from co-workers, and don’t have easy access to other healthcare professionals or a clinical laboratory.

The current healthcare agreement also restricts the flow of patient data between municipal nurses and healthcare centers or hospitals, which are run by the region.

Whenever a nurse finds the need for a physician to assess the patient, she (“most municipal nurses are women”) has to make a phone call, and book a home visit. If it’s daytime, the nurse gets in touch with a general practitioner at the local healthcare center. On evenings and weekends, she contacts a doctor at Falck, a contractor, based some 130 km away.

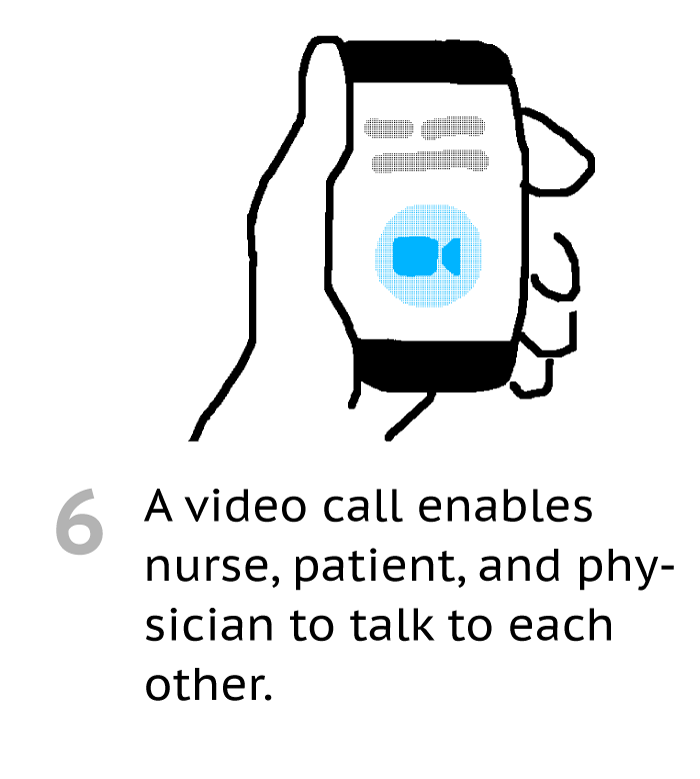

Here, Innovation Skåne saw the opportunity for a service that could enable remote assessment. They wondered: what would this system look like, and what would be the “optimal digital solution” to support it? What does the physician need, to assess a patient remotely? To make it possible, what tools should the nurse have at hand when visiting the patient?

Fieldwork

To get to know the viewpoints of different stakeholders, we used qualitative methods, including:

- two semi-structured, face-to-face interviews with two municipal nurses in the north of Skåne

- a telephone interview with a general practitioner working at a nearby primary care center

- a telephone interview with a medically responsible doctor at Falck

- a face-to-face interview with a digitalisation strategist and former doctor at Region Skåne who is working on a digital healthcare center project

- a face-to-face interview with a physician on the mobile doctors’ team at the local hospital

- a 1½ hour long co-design workshop with three municipal nurses

The interviewees directly involved in homecare helped us grasp the habits and routines of their daily work, and enabled us to visualise what goes into a nurse’s home visit.

“If you do a CRP test – suspecting, for instance, erysipelas – then you can start treating the patient, and the doctor doesn’t need to come, and the patient doesn’t need to go to the hospital.”Municipal nurse

“The cases we meet when visiting patients just couldn’t be diagnosed remotely.”Medically responsible doctor at Falck

Differing views on remote assessment

One of our key findings was that nurses and physicians fundamentally differed in how they viewed the possibility of remote assessment in homecare.

The nurses seemed positive towards the idea, assuming it could lead to patients getting faster treatment. In the nurses’ words, each of the tools enabling diagnosis over distance could add “a piece of the puzzle”, which, when combined, would reveal “the whole picture”.

Still, while they accepted that it would mean a change in routines, the nurses did fear the increased responsibility that the tools may bring along with them.

The two doctors we spoke to saw no place for remote assessment in their type of practice, believing that it would deprive them of the opportunity to examine the patient as closely as needed. Neither one thought that any of the home visits they make today could have been avoided.

It appeared that, before being able to collaborate remotely, nurses and physicians would actually have to be in the same place and talk to each other. We came to believe that the value we could bring as designers in this project was making clear why a participatory approach was needed – rather than coming up with “innovative ideas” or “optimising the solution”.

“I don’t find video consultations appealing, because I can’t touch, smell, twist and turn the patient. I’m left with two senses only.”General practitioner at a primary care center

“The more we can do, the clearer the patient picture becomes, but you also have to consider what we’re supposed to do with that data. How much responsibility is put on us?”Municipal nurse

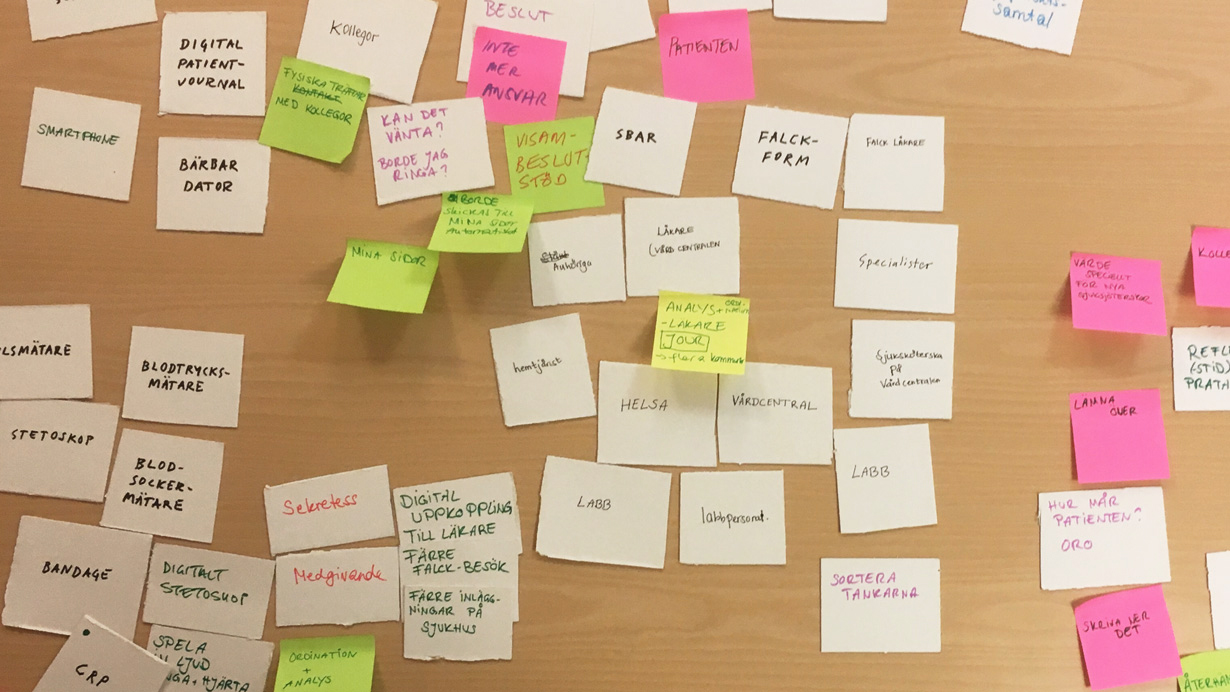

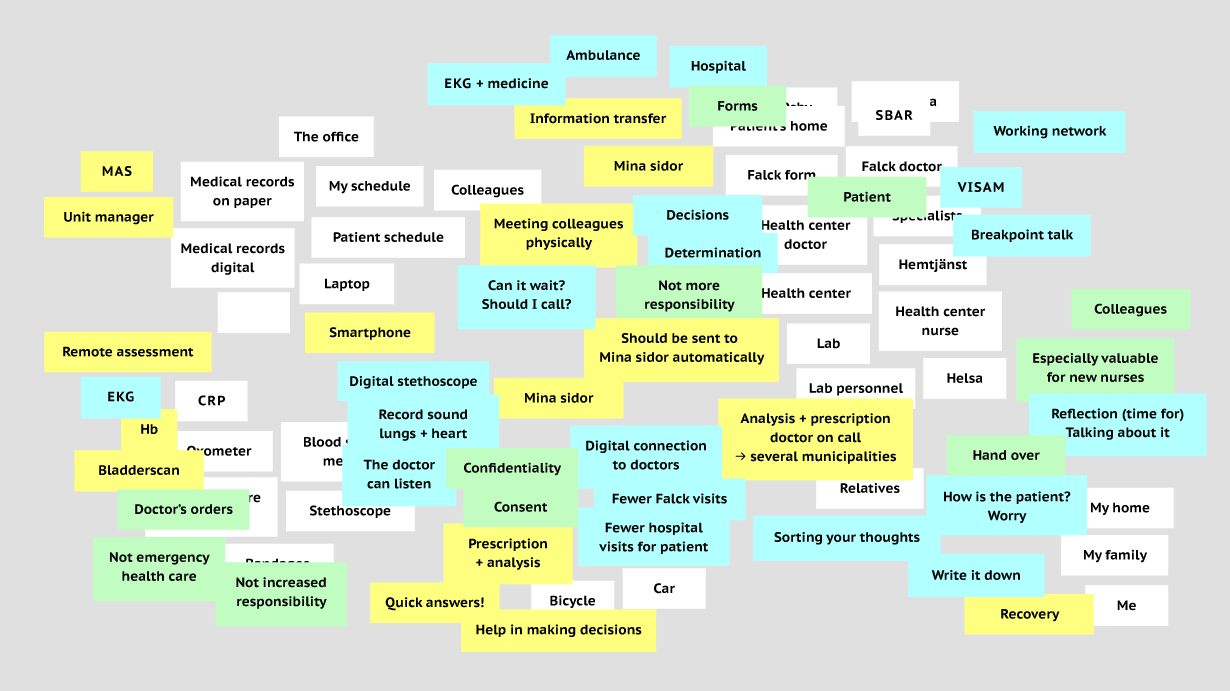

Co-design workshop

The co-design workshop was aimed at identifying gaps surrounding the nurses’ job in the current system by imagining an ideal future. One member of our group acted as workshop facilitator.

During the workshop, we presented the nurses with paper cards that included objects, places and people related to their work routine. By interacting with these cards – writing new ones, rearranging their order and placement, or taking them off the table – the participants could examine their current journey and workflow, and imagine ways to improve their job as nurses.

Outcome

The first thing on our list of recommendations for Innovation Skåne was a longer, deeper, and more structured participatory project, involving nurses, physicians, and other key actors. In order to make a service of this complexity happen, we believed the stakeholders would have to be included from an early stage – not merely to inform the outcome, but as co-designers to some degree.

Along with these suggestions, we presented a prototype showing how the service might work. Made on a smartphone, the storyboard and animation were intentionally rough, so as not to make the scenario seem fixed and unchangeable, but rather function as a starting point for a discussion between stakeholders.

Since we were encouraged to look even further into the future of remote assessment, we provided our informed guesses, touching upon the role of artificial intelligence, haptic interaction, augmented and virtual reality, and wearable or swallowable devices.

Finally, we pointed to a number of potential problems to consider, which included: a loss of bodily skills among physicians, security and privacy issues when dealing with sensitive data, the disruption of patient-doctor continuity, and the difficulty of translating nuanced qualities of human interaction into digital technology.